Introduction to the MEMP Translations

The Devon port of Exeter possesses the best extant medieval series of local customs accounts in Europe.[1] Such local accounts rarely survive, which makes the Exeter series even more unusual since it covers almost 70 per cent of the years from 1300 to 1500.[2] The Exeter accounts do not record exports but do keep careful track of all incoming ship traffic, by coast or from overseas. In contrast, the well-known English national customs accounts (TNA E122) only record overseas trade, that is, ships that arrived directly from overseas, thus missing the bulk of sea-going trade, which was by coast.[3] For each ship entry, the Exeter accounts usually record: the arrival date, the ship’s name, type, home port and master; the importers, their custom status and custom owed (if any); and the type and quantity of goods they imported.

The aim is to include translations on MEMP of all the extant accounts; those currently available are noted in the list of Extant Local Port Customs Accounts for Exeter.

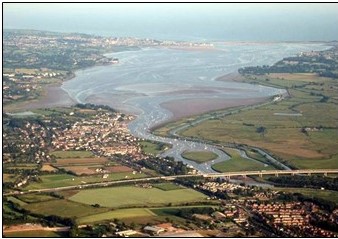

Ships coming to Exeter docked at its outport in Topsham, four miles south of the city at the head of the Exe estuary. The unusually careful documentation of the goods arriving at the port stems in large part from the requirement (dating from at least the 1170s) that Exeter pay one-third of the customs on wine imports to the seigneurial lord of Topsham, the earl of Devon. This division of profits also explains why the earliest surviving accounts were often divided into two accounts: one for wine and one for other merchandise. Further information on the evolution of the Exeter customs system, the procedures of collection, the rates assessed, exemptions, and the ships, mariners, and cargoes of the first fifty plus years of extant accounts are in the “Introduction” to The Local Customs Accounts of the Port of Exeter, 1266 to 1321. See also the Glossary of Weights and Measures used in the Exeter local port customs accounts.

Because the Exeter customs accounts are highly formulaic, the MEMP translations are reproduced in a tabular format that largely follows the order of items in the original entries; the format is adopted from the print edition of the accounts for 1266 to 1321. An example of the format and language of the original accounts can be found in the Latin transcript of the account for 1310/11.

The following editorial principles (mostly adopted from the print edition) have been followed.

Editorial interventions are in square brackets. Empty square brackets indicate a blank space in the manuscript. Illegible words are indicated by three stops (…). When the transcripton is uncertain, a ? is appended; if the translation is uncertain, the ? is accompanied by the Latin is enclosed in square brackets. An apostrophe has been used to represent scribal marks that are not easily transcribed; these mainly come at the end of words to indicate the case ending.

Punctuation in the originals tends to be inconsistent and is often lacking altogether. Punctuation has been added to improve the clarity of the translation but has been kept to a minimum in favor of the tabular format. The wording in the final Custom line was written in the left-margin, but the wording after the semi-colon (which usually offers the name of the pledge for the custom) comes after a semi-colon.

Emendations to the original text are indicated when words have been crossed through, underlined, or obviously erased (noted in a footnote). Later additions using a different ink or hand have only been singled out with curly brackets in the accounts that originally appeared in the print edition (1266-1321), but are rarely marked in the other translations since the later accounts were often written in several different hands. Additions or corrections made with superscripts above the line (often with a carat indicating the location of the insertion) are noted within round brackets. Many of these superscripts note the custom amount paid or the status of the importer; ‘free’ [lib‘] indicates that the importer is free of custom, a privilege extended not only to members of Exeter’s freedom of the city, but also to individuals who belonged to the freedom of places (like London or the Cinque Ports) that enjoyed exemptions from customs by virtue of royal charters.

Ship-names are preserved as written in the original account but italicized. The definite article that often precedes the ship-name is retained in the original and italicized. The ship-type is translated into modern English unless is is part of the ship-name.

Place-names are anglicized and modernized, but the Latin is often given in square brackets when the original spelling and modern English vary significantly. Unidentified place-names are italicized. See the Bibliography of Place-Names and Cargoes below for the sources used to identify the home ports of ships in the Exeter PCA.

Personal names: forenames have been modernized, but surnames have been left in the original (nominative) spellings.

Numerals written as Roman in the manuscript are here rendered as Arabic. Money amounts are transcribed as they appear in the account, using the following abbreviations: £ (libra/pound), s (solidi/shilling), d (denarius/penny), ob (obolus/half-penny), q (quarterium/farthing). There were 20s and 240d in £1 and 12d in 1s.

Dates are supplied in modern form, except for those stated in the headings to the accounts, which employs ‘Michaelmas’ for ‘the feast of St Michael the archangel’ (29 September), which was the beginning of the accounting year used in the Exeter and most medieval English accounts. These fiscal years are noted with a slash separating the two years (e. g., 1395/96); years separated by a dash indicate a period within the two years. When a ship entry was dated as eodem die, the date of the previous entry was used and [the same day] inserted next to the Docked date.

Cargoes are usually translated without prepositions to save space, thus ‘9 tuns of wine and 4 pipes of wine’ is rendered as ‘9 tuns 4 pipes wine’. A glossary will eventually be added to this site, but for the meantime, see the Bibliography for Place-Names and Cargoes, below, for the main sources used to identify imports.

Weights and measures have all been translated except for those with no known English equivalent. C and M are used here to mean either the hundredweight and thousandweight, or the hundred and thousand by tale for commodities that are not expressed in any other measure because in some instances (such as for many types of fish), the ‘long hundred’ of 120 by tale was being referenced. See also the Glossary of Weights and Measures.

Cite this page as: M. Kowaleski, “The Exeter Local Port Customs Accounts: Introduction to the MEMP Translations,” Medieval England Maritime Project (Bronx, NY: Fordham University, 2024), https://memp.ace.fordham.edu/introduction-to-exeter-local-port-customs-accounts/.

Bibliography for Place-names and Cargoes

- Cobb, H. S. “Glossary and Index of Commodities.” The Local Port Book of Southampton for 1439-40. Southampton Record Series, 5. Southampton, 1961, pp 117-26. [an online copy can be borrowed for one hour at archive.org]

- Cobb, H. S. “Glossary and Index of Commodities.” The Overseas Trade of London. Exchequer Customs Accounts 1480-1. London Record Society, 27. London, 1990, pp. 174-89.

- Ekwall, Eilert. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford, 4th edn, 1960.

- Gover, J.E.B., A. Mawer and F. J. Stenton. The Place-Names of Devon. 2 vols. Cambridge, 1931-32, reprint 1986.

- Mollat, Michel.” “Index des noms de lieux” and “Index analytique.” Le commerce maritime normand à la fin du moyen âge. Paris, 1952, pp 567-91.

- Padel, O. J. A Popular Dictionary of Place-Names. Penzance, 1988.

- Touchard, Henri. “Annexe XIII: Glossaire des noms de marchandises, mesures, métiers” and “Annexe XIV: Indes des Noms de Lieux,” in “Les douanes municipales d’Exeter (Devon). Publication des roles de 1381 à 1433. Thèse complémentaire pour le Doctorat ès lettres. Université de Paris, 1967, pp 375-99.

- Touchard, Henri. “Index des Noms de Lieux.” Le commerce maritime Breton à la fin du moyen âge. Paris, 1967, pp 431-48.

[1] For port customs accounts in Europe, see M. Kowaleski, “Sources for Medieval Maritime History, in Reading Primary Sources: The Interpretation of Texts from the Middle Ages, ed. J. Rosenthal (London and New York, 2011), pp. 149-62. For a comprehensive list of local port customs accounts in medieval England that are in print or online, see “ Editions of Port Customs Accounts,” Medieval England Maritime Project, ed. M. Kowaleski (Fordham University, 2024). In the middle ages, Exeter was a cathedral city, customs head port, and administrative center for southwestern England, whose population in the early fourteenth century was about 5000, but fell to c. 3100 in the late fourteenth century, rising to c. 7000 according to the Tudor subsidy of 1525; see M. Kowaleski, Local Markets and Regional Trade in Medieval Exeter (Cambridge, 1995) pp 9-10, 325-6, 371-4.

[2] From 1266 to 1302, ship arrivals and cargoes were often noted on the dorses of the Exeter Mayor’s Court rolls (at the Devon Heritage Centre); thereafter they were registered on separate rolls. See the list of Extant Local Port Customs Accounts for Exeter.

[3] It is estimated that three-quarters of shipping activity and well over half of the value of sea trade to Exeter arrived by coast; Kowaleski, Local Markets and Regional Trade in Medieval Exeter, pp. 227-32.